This is the third part of my thoughts on the design of small gardens.

The other parts can be reached by clicking on these links ...

Part 1 - an introduction to why small gardens need designing;

Part 2 - lose the boundaries, borrowed views & landscape, using 3 dimensions;

Part 3 follows, covering keep it simple, maximise space usefulness, optical illusions;

Part 4 - keep it interesting, growing for the table and utility issues.

Here goes ...

4. Keep it simple!In a small space it’s best to stick to simple, bold

shapes – definite circles, rectangles & arcs, rather than serpentine, organic shapes which need space to allow one’s eye to follow their sweep. If the plot is an odd shape use the “

lose the boundaries” approach, as described in part 2 of this series, to re-shape it so that the space within the planting has simpler, more definite geometry. This also makes it look thought about when compared to a patch of lawn or gravel “left over” from the shape of the other features.

Don't try to cram in too much - if each direction that you look in has several focal features competing for your attention, there's no restfulness and the whole thing becomes cluttered and feels cramped. Try to keep the main functional spaces open with low-level planting and features.

In similar vein, avoid too many variations in materials - “less is more”. Using the same basic surfacing throughout (i.e. the deck / patio / paths) will unify the space and make it seem larger than one which has timber & paving & gravel & brick & stone & concrete & grass, etc. This works in much the same way that having the doors open and the same flooring throughout a small house can make it seem larger.

5. Maximise the usefulness of space:

Do you really need that bit of lawn?

OK, you need a flat surface for practical usage like sitting and dining spaces, as well as the aesthetic purpose of balancing the planting masses, and a change of texture fr

om deck or paving can add interest – but that can be achieved with gravel or slate chips or, better still, with a pebble/cobbles mix to give more interesting variation in texture - perhaps planted through with small ornamental grasses or perennials around a focal point boulder, bird bath or sculptural piece.

Grass is quite poor ecological value and takes a lot of chemical & water input to remain a good lawn throughout the year – as well as a lot of work.

It can become really tedious to get a mower out for a very small lawn!

In a small garden you may still have distinct areas – dining/BBQ, sun-lounging, shady seating for reading, chatting & socialising. You might achieve this with a very simple rectangular shape which has some parts “cut away” – this adds interest to the shape & sub-divides it to create the various functional areas. The cut-aways could be features such as a firepit or BBQ, herb bed, raised planter, water feature, etc.

If the space is really small, consider using

“built-in” features, rather than free-standing ones, to keep the space open for movement and allow you to bespoke the size & scale of the features.

If the plot is long & narrow, or short & wide, setting the main rectangular shapes diagonally, rather than parallel to the house, can increase the apparent length of the shorter dimension. A long, narrow space can also be made to seem less like a corridor by using planting or trellising to partially separate sections of the length into “rooms”, perhaps with views framed through archways to focal features in the next room, so creating the “what’s down there?” added interest.

Do you really need paths connecting the areas, or could a path be “suggested” along the edge of a shape or by stepping stones? When planning the arrangement, remember that a narrow strip encourages brisk movement along the line, a wider strip is still “directional”, but allows a more leisurely pace of transition – whereas a squared (or circular) shape suggests a lack of movement, i.e. a resting place such as a patio.

If you have a flat, or shallow-pitched, garage, shed or house extension, why not consider a green roof (

click here for more information) to add more planting space & ecological value?

6. Exploit optical illusions: This is a biggy!

The directional effect of shapes described above can also work with materials, such as the laying patterns for brickwork / paving and especially for decking. The human brain is always looking for patterns and the eye will tend to follow linear features – so a deck with boards running across the line of sight will emphasize the width of the space, whilst having the boards running with the line of sight will emphasize its length. This effect is seen in clothing design, where striped vs. hooped patterns complement different figures.

Laying deck boards diagonally can make a much more interesting scheme, especially if combined with a change to the opposite diagonal on a split-level deck – and can serve to direct the eye to a focal feature. It’s also practical in that boards are cut obliquely to fit the edges so, if they aren’t perfectly square to the adjacent building walls, there’s no “run out” gap which looks dreadful.

Using horizontal linear timber strips instead of conventional square or diamond pattern trellis for screens also has this directional aspect and can “stretch” a short boundary.

In this example, grooved deck boards are used to give the same effect, and also provide unity with the decked surface.

Other optical “cheats” can be made using

mirrors to create false windows or doors in walls which can add apparent depth and provide that “what’s through there?” appeal.

In this picture they are used in a semi-formal arrangement to break up a dark, unattractive boundary and add the impression of depth beyond.

They also work really well when the mirror edges are concealed by other planting, or within false framing (e.g. “perspective” panels), and the reflection from the mirror is another part of the garden space, not the viewer – i.e. ensure the mirror is angled slightly. A large mirror, perhaps with ivy trailing over it, at the back of an arch can make it appear deeper – more like a pergola offering a walk-through to another part of the garden space.

Mirrors will always need to have a rigid surface to mount them on, both to protect them from cracking and to prevent movement in the wind - so a free-standing mirror needs at least 12mm marine-ply backing, attached to well-fixed posts. If the reflection is to be seen from some distance away (e.g. from inside the house), make sure it’s very optically flat – slight ripples in the glass produce only minor distortion when seen from a few feet distance, but give a “hall of mirrors” nightmare when seen from 20 or 30 feet!

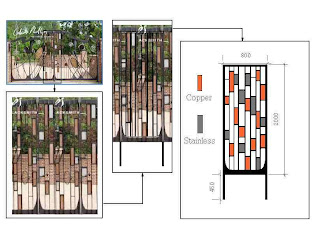

Another optical trick is using a series of vertical poles where the gap between them reduces along the run, and/or, the poles themselves reduce in height & thickness. This produces a very exaggerated perspective which makes the depth along the run look much greater. If you use this beware of the distorted look when viewed from the opposite direction!

Wall

murals may not provide realistic illusions, but can certainly improve the view of a close, uninteresting, neighbouring wall.

Making good decisions with your planting can also help in this optical illusion field.

Bright colours such as orange, yellow & red “advance” – i.e. they seem to jump out at you, so the object appears closer – useful for “shortening” that long, narrow, corridor space. Conversely, muted colours such as blue, mauve, silver/grey and pale green “recede” – making the object appear further away. The effect of colour also changes with the daylight – oranges, reds and yellows “sing out” at dusk, especially when there’s a good red sunset.

Texture has similar visual properties – small-leafed plants provide a “bland” uniform texture which recedes, whereas large-leafed plants with a more open, architectural form advance, making them good focal points. Judicious use of these characteristics, blending in a few advancing features against a receding background can give a greater sense of depth to the view and add to the illusion of space.

The other parts of this series can be reached by scrolling through my blog, or by clicking the links at the top of this post.

Thanks for persevering!

Some plastic mesh (about 1m x 1m), 3 lengths of timber batten about 1.2m (4’) long and a piece of exterior (marine) plywood about 450mm x 350mm (18” x 14”), plus some twist tie and a staple gun.

Use the staple gun to tack the mesh onto the batten.

Designed by Dr. Koichi Kawana, it is a 6.5 acre authentic

Designed by Dr. Koichi Kawana, it is a 6.5 acre authentic  It was peaceful and tranquil on the beautiful day that we were there, and well worth a visit if you’re anywhere in LA. Please check the opening hours carefully, however, before you make a long journey.

It was peaceful and tranquil on the beautiful day that we were there, and well worth a visit if you’re anywhere in LA. Please check the opening hours carefully, however, before you make a long journey.

Once schools have signed up with the Concrete Jungle campaign they can register the dimensions of their garden and use the site to show the progress they are making.

Once schools have signed up with the Concrete Jungle campaign they can register the dimensions of their garden and use the site to show the progress they are making.

If you feed the birds, don't forget to clean the feeders regularly to prevent disease. See the

If you feed the birds, don't forget to clean the feeders regularly to prevent disease. See the